Moloch – Decentralized Incentives and the Emergence of Systemic Crises

[Disclosure: This paper has been written together with AI]

Moloch – Decentralized Incentives and the Emergence of Systemic Crises

29 May 2025

Abstract

This paper presents an analysis of systemic coordination failures—termed "Molochian dynamics" —through multiple interdisciplinary lenses. Drawing from game theory, political economy, institutional design, and Eastern philosophical traditions, we examine how decentralized actors optimizing for narrow self-interest generate collectively suboptimal outcomes without requiring centralized conspiracies or malicious intent. These dynamics manifest across diverse domains, including environmental degradation, geopolitical arms races, technological development races, and financial market instabilities. The paper demonstrates that these seemingly disparate crises share fundamental structural similarities in their incentive architectures and emergent properties.

Our analysis reveals that Molochian traps arise not from individual moral failings but from misaligned incentive structures that reward short-term optimization at the expense of long-term collective welfare. By synthesizing insights from Western game-theoretic frameworks with Eastern philosophical traditions—particularly Confucian ethics—and models such as ASEAN’s consensus-based governance, we develop a conceptual framework for understanding and addressing these systemic failures.

The paper proposes solutions rooted in four complementary approaches:

Technocratic planning mechanisms (e.g., China’s Five-Year Plans) that enable long-term coordination.

Virtue ethics, which cultivates leadership oriented toward relational harmony and collective flourishing.

Game B, a civilizational reset informed by global traditions (Indigenous stewardship, cooperative economics, and decentralized protocols).

Robust feedback systems that facilitate iterative improvement through adaptive governance and polycentric learning.

Through comparative case study analysis spanning environmental, geopolitical, technological, and social domains—including China’s high-speed rail, the U.S.-China chip war, and ASEAN’s consensus-driven diplomacy—we demonstrate both the universality of Molochian dynamics and the context-specific nature of effective interventions. This research aims to contribute to ongoing scholarly debates about institutional design, collective action problems, and the limitations of market-based solutions to complex social challenges. It also highlights the importance of cultural pluralism and hybrid governance models, offering practical insights for policymakers seeking to address systemic crises through pragmatic experimentation that bridges ideological and cultural divides.

Introduction

Historical Context of Moloch

The concept of Moloch has traversed a remarkable evolutionary path from ancient mythology to contemporary analytical frameworks. In its original context, Moloch was a Canaanite deity associated with child sacrifice, symbolizing the terrible price societies might pay for perceived collective benefit. This ancient metaphor has been repurposed throughout history, perhaps most notably by Allen Ginsberg in his 1955 poem "Howl," where Moloch represented the dehumanizing forces of industrial capitalism and militarism. The metaphor gained renewed analytical significance through Scott Alexander's influential 2014 essay "Meditations on Moloch," which reframed Moloch as a personification of coordination failures inherent in complex social systems.

Alexander's work represents a pivotal development in our understanding of systemic failures, as it articulates how rational actors pursuing individual optimization can collectively produce outcomes that none would choose if coordination were possible. This insight transcends simplistic narratives of villainous actors or conspiratorial forces, instead highlighting how harmful outcomes can emerge from structural incentives alone. The present paper builds upon Alexander's foundation by grounding these insights in formal theoretical frameworks and historical examples, providing a more rigorous analytical basis for understanding Molochian dynamics.

The historical trajectory of the Moloch concept reflects a growing recognition that many of humanity's most pressing challenges—from climate change to nuclear proliferation—cannot be adequately addressed through conventional analytical frameworks that focus primarily on individual actors or bilateral conflicts. Instead, these challenges require an understanding of complex systems, emergent properties, and the often counterintuitive relationship between micro-level incentives and macro-level outcomes. By examining the historical evolution of the Moloch concept, we gain valuable perspective on how societies have grappled with coordination problems throughout human history.

Nash Equilibrium and Coordination Failures

At the heart of Molochian dynamics lies the game-theoretic concept of Nash Equilibrium, a state in which each participant, acting rationally according to their individual incentives, has no reason to unilaterally change their strategy—even when the collective outcome is suboptimal or even catastrophic. This mathematical formalization, developed by John Nash in the mid-20th century, provides a powerful explanatory framework for understanding why intelligent, well-intentioned actors might nonetheless become trapped in destructive patterns of interaction.

Climate inaction offers a paradigmatic example of this dynamic. Individual nations face strong incentives to continue carbon-intensive development while free-riding on others' mitigation efforts. The resulting equilibrium—minimal action despite catastrophic warming—reflects not a failure of understanding but a structural misalignment between individual and collective rationality. Similar dynamics manifest across domains, from arms races where security-seeking behavior paradoxically decreases overall security, to market competition where race-to-the-bottom dynamics in labor standards or environmental practices undermine collective welfare.

Daniel Schmachtenberger has characterized these situations as "race-to-the-bottom" competitions, where competitive pressures force actors to optimize for narrow metrics at the expense of broader values. These dynamics are exacerbated by several factors: misaligned incentives that reward harmful externalities, information asymmetries that obscure systemic consequences, and temporal disconnects between immediate rewards and delayed harms. The resulting systems exhibit what systems theorists call "attractor states"—self-reinforcing equilibria that resist perturbation and reform efforts.

The persistence of these harmful equilibria challenges conventional economic wisdom about the efficiency of decentralized decision-making. While markets and other decentralized systems excel at processing certain types of information and coordinating certain types of activity, they systematically fail when confronted with externalities, public goods problems, and other market failures. Understanding these limitations is essential for designing institutions capable of addressing complex collective action problems.

Thesis Statement

This paper advances the thesis that Molochian systems emerge not from malice, conspiracy, or moral failing, but from structural incentives that systematically reward short-term gains over collective well-being. These systems trap even well-intentioned actors in dynamics that none would choose if coordination were possible. Addressing these challenges requires more than marginal policy adjustments or appeals to individual virtue; it demands fundamental redesign of the systems, incentives, and governance frameworks that shape collective behavior.

Our analysis draws particular attention to two promising but underexplored approaches to coordination problems. First, we examine Confucian ethics, with its emphasis on relational harmony, moral cultivation, and the responsibilities of leadership. This tradition offers a compelling alternative to Western liberal individualism, highlighting how virtue-oriented governance might overcome the limitations of purely incentive-based approaches. Second, we consider China's state-led coordination models, which demonstrate how centralized planning mechanisms can enable long-term investments and strategic coordination that market-based systems struggle to achieve.

By integrating insights from Western game theory and institutional economics with Eastern philosophical traditions and governance models, this paper develops a more comprehensive framework for understanding and addressing Molochian dynamics. This interdisciplinary approach recognizes that complex systemic challenges require solutions that transcend the limitations of any single analytical tradition or governance paradigm. The paper thus contributes to ongoing scholarly conversations about institutional design, collective action, and the relationship between individual incentives and collective outcomes in an increasingly complex and interconnected world.

Literature Review

Key Theoretical Foundations

The study of Molochian dynamics draws upon several rich theoretical traditions that have evolved to explain collective action problems and coordination failures. Game theory provides perhaps the most formalized framework for understanding these dynamics, with several canonical models offering particular insight. Garrett Hardin's "Tragedy of the Commons" (1968) articulated how individual rational actors, when sharing a common resource without coordination mechanisms, will tend to overexploit that resource to the detriment of all. This model has proven remarkably versatile in explaining environmental degradation, resource depletion, and other collective action failures. Similarly, the Prisoner's Dilemma, formalized by Anatol Rapoport and Albert Tucker in the 1950s, demonstrates how individually rational decisions can lead to collectively irrational outcomes when cooperation cannot be enforced. These game-theoretic models provide mathematical precision to the intuitive concept of Molochian traps.

Elinor Ostrom's groundbreaking work on governing common-pool resources significantly advanced our understanding of how communities can overcome these coordination challenges. Her research, culminating in her 1990 book "Governing the Commons," demonstrated that neither pure market solutions nor top-down state control were necessary or sufficient conditions for sustainable resource management. Instead, Ostrom documented numerous cases where local communities developed sophisticated institutional arrangements that enabled successful coordination. Her work on polycentric governance—systems with multiple centers of decision-making authority—offers particularly valuable insights for addressing complex, multi-level coordination problems that characterize many contemporary Molochian dynamics.

In the realm of political economy, competing theoretical traditions offer contrasting perspectives on coordination problems in international relations and political systems. Neoliberal institutionalism, associated with scholars like Robert Keohane and Joseph Nye, emphasizes how international institutions and regimes can facilitate cooperation even in an anarchic international system. This tradition highlights the potential for incremental institutional reform to address coordination failures. In contrast, structural realism, exemplified by Kenneth Waltz's work, emphasizes how the anarchic structure of the international system creates security dilemmas and other coordination problems that are extremely difficult to overcome without fundamental structural change. These competing frameworks offer complementary insights into the persistence of Molochian dynamics in international relations.

Critical political economy traditions, including Marxist analysis and various critiques of market fundamentalism, provide additional perspectives on how capitalist systems generate coordination failures. These traditions emphasize how market mechanisms, while efficient at coordinating certain types of activity, systematically fail to account for externalities, public goods, and other market failures. Moreover, they highlight how power asymmetries within economic systems can lead to institutional arrangements that systematically benefit certain actors at the expense of collective welfare. These critiques challenge the assumption that decentralized market mechanisms will naturally produce optimal outcomes, instead highlighting the need for deliberate institutional design to align individual incentives with collective welfare.

Confucian ethics offers a distinctive philosophical tradition that addresses coordination problems from a virtue-ethical perspective rather than through institutional design alone. Confucian thought emphasizes harmony (和, hé) as a central social value, achieved not through uniformity but through the proper balancing of diverse elements. This tradition places particular emphasis on moral leadership (君子, jūnzǐ) and the cultivation of virtue as prerequisites for social harmony. The Confucian concept of social roles (禮, lǐ) provides a framework for understanding how individual behavior should be oriented toward collective flourishing rather than narrow self-interest. This tradition offers a compelling alternative to Western liberal individualism, highlighting how virtue-oriented governance might overcome the limitations of purely incentive-based approaches to coordination problems.

Critiques of Molochian Frameworks

While Molochian frameworks provide powerful explanatory tools for understanding coordination failures, scholars have identified several important limitations and critiques of these models. Perhaps most fundamentally, real-world actors are often not fully rational in the sense assumed by classical game theory. Behavioral economics and psychological research have documented numerous cognitive biases and heuristics that lead human decision-makers to deviate from the predictions of rational choice models. These deviations can sometimes exacerbate coordination problems, as when present bias leads to underinvestment in long-term collective goods. In other cases, however, pro-social preferences and norms of reciprocity can enable cooperation even in situations where rational choice models would predict defection.

Institutional scholars, building on Ostrom's work, have demonstrated that well-designed institutions can mitigate coordination failures through various mechanisms. These include establishing clear boundaries and rules, creating monitoring and enforcement mechanisms, developing conflict resolution processes, and ensuring that those affected by rules can participate in modifying them. This research challenges the fatalism sometimes associated with Molochian narratives, highlighting how thoughtful institutional design can enable successful coordination even in challenging contexts. The diversity of institutional arrangements that have successfully governed common-pool resources suggests that there is no single optimal solution to coordination problems; rather, effective institutions must be tailored to specific social, ecological, and cultural contexts.

Critics have also noted that Molochian frameworks sometimes overstate the inevitability of coordination failures by neglecting the role of communication, trust-building, and social learning in enabling cooperation. Experimental research has consistently shown that allowing participants to communicate before making decisions dramatically increases cooperation rates in social dilemma games. Similarly, repeated interactions create opportunities for the evolution of cooperative norms and reputation-based enforcement mechanisms. These findings suggest that coordination failures are not inevitable consequences of structural incentives but contingent outcomes that can be influenced by social processes and deliberate intervention.

Feedback mechanisms have emerged as a critical element in addressing coordination problems, enabling systems to adapt and evolve in response to changing conditions and new information. Iterative policy evaluation, adaptive management approaches, and other learning-oriented governance mechanisms allow for the continuous refinement of institutional arrangements in response to their observed effects. This emphasis on feedback and adaptation contrasts with static institutional models that assume optimal arrangements can be designed in advance. Instead, it suggests that addressing complex coordination problems requires ongoing processes of experimentation, evaluation, and adjustment based on observed outcomes.

These critiques do not invalidate Molochian frameworks but rather enrich them by highlighting the contingent nature of coordination failures and the diverse mechanisms through which they might be addressed. By integrating insights from behavioral economics, institutional analysis, and adaptive governance, we can develop more nuanced understandings of how Molochian dynamics emerge and how they might be overcome through a combination of institutional design, norm cultivation, and iterative learning processes.

Conceptual Framework

Defining Molochian Systems

A Molochian system can be defined as a socio-economic or political arrangement characterized by three essential features that together create persistent coordination failures. First, these systems involve multiple actors optimizing for narrow incentives such as profit maximization, power accumulation, or status competition. These actors may be individuals, corporations, nation-states, or other entities capable of strategic decision-making. Crucially, their optimization processes are typically rational within the constraints of their local information and incentive structures, yet collectively produce outcomes that none would choose if coordination were possible.

Second, Molochian systems are characterized by externalities and feedback loops that reinforce harmful equilibria. Externalities occur when the costs or benefits of an action are not fully borne by the decision-maker, creating a misalignment between individual incentives and collective welfare. Positive feedback loops amplify initial conditions, potentially leading to runaway dynamics that resist correction. For example, in social media ecosystems, engagement-maximizing algorithms promote polarizing content, which increases user engagement, which in turn reinforces the algorithmic preference for such content. This self-reinforcing cycle can lead to extreme polarization and information siloing despite no individual actor explicitly desiring this outcome.

Third, Molochian systems exhibit a distinctive governance structure in which no single actor controls the system, yet all are trapped within it. This distinguishes Molochian dynamics from simple hierarchical power structures or explicit coordination problems. Even powerful actors within Molochian systems find their options constrained by competitive pressures and systemic incentives. For instance, corporate executives who might personally value environmental sustainability nevertheless face strong pressures to prioritize short-term profits due to shareholder expectations, competitive dynamics, and compensation structures tied to quarterly performance. This distributed entrapment makes Molochian systems particularly resistant to reform, as even well-intentioned actors with substantial resources find their ability to effect change severely constrained.

These three features—narrow optimization, reinforcing feedback loops, and distributed entrapment—create systems that exhibit emergent properties distinct from the intentions of any constituent actor. Understanding these emergent properties requires moving beyond methodological individualism to examine how system architecture shapes collective outcomes. This perspective draws on complex systems theory, which emphasizes how simple rules of interaction can generate complex, often unpredictable macro-level patterns. By identifying the structural similarities across diverse domains, from environmental degradation to arms races, we can develop more effective interventions that address root causes rather than merely treating symptoms.

Mechanisms of Failure

Molochian systems fail through several interrelated mechanisms that transform individually rational decisions into collectively irrational outcomes. Perverse incentives represent perhaps the most fundamental mechanism, creating situations where actions that generate negative externalities are rewarded while those that would benefit the collective are punished. Fossil fuel subsidies exemplify this dynamic, artificially lowering the cost of carbon-intensive energy production and consumption while undermining the economic viability of renewable alternatives. Similarly, in academic publishing, citation metrics that reward novelty and positive results create incentives for researchers to pursue flashy but potentially unreproducible work rather than crucial replication studies or negative results that would advance scientific knowledge more effectively.

Path dependency constitutes another critical mechanism through which Molochian systems resist reform. Once institutions, technologies, or social practices become established, they tend to persist due to increasing returns, sunk costs, and complementary investments. Corporate governance structures centered on shareholder primacy, for instance, have become deeply embedded in legal frameworks, business education, and cultural expectations, making alternative models difficult to implement despite growing recognition of their limitations. Similarly, carbon-intensive infrastructure creates lock-in effects that perpetuate fossil fuel dependence long after cleaner alternatives become economically viable. These path dependencies mean that even when the harmful consequences of current arrangements become apparent, transitioning to alternative systems faces substantial resistance.

Feedback loops represent a third crucial mechanism that can amplify initial conditions and create self-reinforcing dynamics. Positive feedback loops accelerate change in a particular direction, potentially leading to runaway effects that overwhelm corrective mechanisms. For example, wealth concentration creates political influence that can be used to secure policies favorable to further wealth concentration, creating a self-reinforcing cycle of inequality. Negative feedback loops, by contrast, dampen change and maintain system stability, sometimes preserving harmful equilibria despite attempts at reform. The interaction between positive and negative feedback loops creates complex system dynamics that can be difficult to predict or control.

Information asymmetries and cognitive limitations further exacerbate these mechanisms of failure. Decision-makers often lack complete information about the consequences of their actions, particularly regarding complex, delayed, or diffuse effects. Even when information is theoretically available, cognitive biases such as present bias, availability heuristics, and scope insensitivity can prevent optimal decision-making. These information and cognitive constraints are not merely individual limitations but systemic features that shape collective outcomes. For instance, the complexity of global supply chains obscures environmental and labor conditions, making it difficult for consumers to make informed choices even when they value ethical production.

Together, these mechanisms—perverse incentives, path dependency, feedback loops, and information constraints—create robust systems that resist reform despite producing outcomes that few would explicitly choose. Understanding these mechanisms is essential for designing interventions that can effectively address Molochian dynamics rather than merely treating their symptoms. By identifying the specific mechanisms operating in particular contexts, we can develop targeted interventions that address root causes rather than merely responding to surface manifestations of deeper systemic failures.

Case Studies of Systemic Coordination Failures

Neoliberalism's Evolution: From Ideology to Systemic Crisis

The evolution of neoliberalism offers a compelling case study of how initially well-intentioned ideas can transform into Molochian dynamics that harm the very systems they were meant to improve. Neoliberalism began not as a political slur but as a specific intellectual project in the 1930s and 1940s, championed by thinkers like Friedrich Hayek who were responding to the economic devastation of the Great Depression and the rise of totalitarian states.

Hayek's seminal work, "The Road to Serfdom" (1944), argued that centralized economic planning inevitably leads to tyranny. The market, in his view, was not merely an economic mechanism but an epistemological tool—a way of processing distributed knowledge that no central planner could possibly possess. This intellectual foundation positioned the market as the ultimate arbiter of value and truth, a premise that would have profound consequences as neoliberal ideas gained political traction.

The transformation of neoliberalism from academic theory to dominant policy framework occurred gradually through the 1970s and 1980s. The stagflation crisis of the 1970s created an opening for neoliberal ideas as Keynesian approaches appeared to fail. Under Margaret Thatcher in the UK and Ronald Reagan in the US, neoliberal policies—deregulation, privatization, tax cuts, and weakening of labor unions—became the new orthodoxy. What began as a reaction against perceived government overreach evolved into a comprehensive worldview that recast all human activity in market terms.

By the 1990s, even nominally left-wing parties had embraced core neoliberal premises. Bill Clinton's declaration that "the era of big government is over" and Tony Blair's "Third Way" represented not just political compromises but the internalization of market logic within progressive politics. The Washington Consensus extended neoliberal policies globally through structural adjustment programs that often prioritized fiscal discipline and market liberalization over social welfare.

The consequences of this ideological shift have been profound and often perverse. As Stephen Metcalf noted in The Guardian, neoliberalism transformed our conception of ourselves: "You see how pervasively we are now urged to think of ourselves as proprietors of our own talents and initiative, how glibly we are told to compete and adapt. You see the extent to which a language formerly confined to chalkboard simplifications describing commodity markets (competition, perfect information, rational behavior) has been applied to all of society."

The 2008 financial crisis represented a critical inflection point. The collapse revealed the inherent instability of deregulated financial markets and the dangers of treating complex social systems as self-regulating markets. Yet despite this apparent refutation of neoliberal premises, the policy response in many countries doubled down on austerity measures that further eroded social safety nets while protecting financial institutions deemed "too big to fail."

Today, we witness the culmination of these contradictions. Income inequality has reached levels not seen since the Gilded Age, with the top 1% in the United States now holding more wealth than the bottom 90%. Labor's share of national income has declined steadily across developed economies. Public goods from education to infrastructure have deteriorated under chronic underinvestment. And perhaps most tellingly, public trust in institutions has collapsed, fueling populist movements that often target the symptoms rather than the underlying systemic causes.

The neoliberal era thus represents a classic Molochian dynamic: a system that no individual actor designed with malicious intent, yet one that collectively produces outcomes that serve neither the long-term interests of capital nor labor. Business leaders who might personally value social cohesion and environmental sustainability nevertheless face competitive pressures to maximize short-term profits. Politicians who recognize the need for public investment face electoral incentives to cut taxes and spending. And ordinary citizens who might prefer a more equitable society find themselves competing ever more intensely for diminishing rewards.

This case illustrates how ideas that begin as intellectual responses to real problems can evolve into self-reinforcing systems that resist reform even when their contradictions become apparent. The neoliberal turn was not a conspiracy but an emergent property of distributed decisions made by actors responding to the incentives before them—a perfect illustration of the Molochian dynamics this paper seeks to analyze.

The US-China Chip War: Mutual Destruction in High Technology

The ongoing semiconductor conflict between the United States and China exemplifies how security-seeking behavior by rational actors can produce collectively harmful outcomes. This "chip war" has evolved from targeted restrictions to a comprehensive technological decoupling that threatens to fragment the global innovation ecosystem, harming both countries and the broader world economy.

The conflict began in earnest in 2019 when the Trump administration placed Huawei on an export control list, cutting the Chinese telecommunications giant off from critical U.S. semiconductor technology. What started as a targeted action against a single company has since expanded dramatically. In October 2022, the Biden administration imposed sweeping controls on the export of advanced semiconductors and chipmaking equipment to China, with the stated goal of impeding Chinese capabilities in artificial intelligence and supercomputing. These controls were tightened further in October 2023 and December 2024, and similar restrictions were implemented by U.S. allies.

The strategic logic behind these restrictions is clear: semiconductors represent a foundational technology for economic and military power in the 21st century. U.S. policymakers fear that allowing China access to cutting-edge chip technology could enable advances in AI and military applications that threaten American security interests. From this perspective, export controls represent a rational response to a genuine security dilemma.

China's response has been equally rational from its perspective: an all-out, government-backed effort to achieve self-sufficiency in semiconductor design and production. The results have been remarkable. Huawei, which many analysts predicted would collapse without access to U.S. technology, has instead developed indigenous alternatives. By 2024, Huawei launched new products featuring advanced semiconductors produced by China's Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation (SMIC). The company's current generation smartphone, the Pura 70 series, incorporates 33 China-sourced components and only 5 from outside China.

This pattern extends beyond Huawei. ChangXin Memory Technologies has made significant inroads into the memory chip market, increasing China's global market share from virtually zero to 5 percent in just five years. Alibaba Group's research arm unveiled the C930 central processing unit in February 2025, based on the open-source RISC-V architecture that provides an alternative to U.S.-controlled designs.

The collective outcome of these rational security-seeking behaviors is increasingly harmful to both countries, in particular to the US. U.S. semiconductor companies have lost substantial revenues from their China sales, reducing the funds available for research and development that drives innovation. The restrictions have also diminished these companies' visibility into Chinese technological developments, potentially leaving them blindsided by breakthroughs. Meanwhile, the fragmentation of global supply chains increases costs and reduces efficiency for the entire semiconductor ecosystem.

The broader implications extend beyond the two countries directly involved. The semiconductor industry has historically thrived on global collaboration and specialization, with different regions focusing on their comparative advantages. The current trajectory threatens to replace this efficient global ecosystem with redundant, subscale national champions protected by government subsidies and trade barriers. The resulting inefficiencies will likely slow the pace of innovation and increase costs for consumers and businesses worldwide.

This case illustrates how security dilemmas can create Molochian traps even when all actors behave rationally according to their individual incentives. Neither the United States nor China wants a fragmented, less innovative technological ecosystem, yet their mutual security concerns drive them toward precisely this outcome. Breaking this dynamic would require institutional innovations that address legitimate security concerns while preserving beneficial technological cooperation—a challenge that neither side has yet solved.

The UnitedHealthcare CEO Incident: Healthcare's Molochian Crisis Exposed

The December 2024 killing of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson and the subsequent public reaction revealed the profound dysfunction in the American healthcare system—a textbook example of Molochian dynamics where individually rational actions produce collectively harmful outcomes that serve neither patients nor the system itself.

Thompson, a 50-year-old father of two, was shot and killed in what police described as a targeted attack while walking to an investor conference in Manhattan. While investigators have not identified a clear motive, the incident unleashed an unprecedented wave of public reaction that exposed the deep wells of anger toward the health insurance industry.

What made this case remarkable was not just the tragic violence itself but the subsequent social media response. As news of the killing spread, tens of thousands of people expressed either support for the act or a disturbing lack of sympathy. "When you shoot one man in the street it's murder. When you kill thousands of people in hospitals by taking away their ability to get treatment you're an entrepreneur," wrote one social media user, capturing a sentiment echoed across platforms.

This reaction reflects the profound misalignment between the incentives facing health insurers and the needs of patients. UnitedHealthcare, like other major insurers, has faced numerous lawsuits and regulatory actions over allegedly denying claims to maximize profits. Nearly 60% of insured Americans surveyed by the Kaiser Family Foundation reported experiencing problems with their health insurance, such as denied claims or difficulties with provider networks. Among those who saw a doctor more than 10 times in the previous year, nearly one-third encountered prior authorization requirements—insurer approvals needed before services are covered.

The industry defends these practices as necessary to prevent fraud and unnecessary care. But research shows they often lead patients to abandon or delay needed treatment. A particularly striking example emerged just before the Thompson incident, when Anthem Blue Cross Blue Shield plans in Connecticut, New York, and Missouri decided to cover anesthesia services for only a limited number of minutes per procedure starting in 2025—a move the American Society of Anesthesiologists called "appalling behavior by commercial health insurers looking to drive their profits up at the expense of patients and physicians providing essential care."

What makes this situation a classic Molochian trap is that individual actors are responding rationally to the incentives they face. Insurance executives have fiduciary duties to maximize shareholder value and face competitive pressures to control costs. Physicians and hospitals, operating in a fee-for-service environment, have incentives to maximize billable services. Pharmaceutical companies rationally price drugs to recoup research investments and maximize returns. And patients, lacking both price transparency and meaningful choice, cannot exercise the kind of consumer sovereignty that might discipline the market.

The result is a healthcare system that costs nearly twice as much per capita as those in other developed nations while delivering worse outcomes on many measures. Administrative costs consume about 34% of U.S. healthcare spending, largely due to the complexity of the insurance system. And despite this enormous expenditure, millions of Americans remain uninsured or underinsured, facing financial ruin if they experience serious illness.

The public reaction to Thompson's killing—while morally troubling in its apparent endorsement of violence—reveals the depth of frustration with a system that seems impervious to reform. As one industry observer noted, "People who are healthy and don't have to use their coverage a lot, they see how much it can cost if you don't have insurance. There's a phenomenon of people feeling grateful that they have coverage at all."

This case illustrates how Molochian systems can persist despite producing outcomes that virtually no one would choose if coordination were possible. Patients want affordable, accessible care; providers want to deliver quality care without bureaucratic interference; insurers want sustainable business models; and society wants a healthy population. Yet the interaction of these actors within the current institutional framework produces a system that fails to achieve any of these goals effectively.

China's High-Speed Rail: State-Led Coordination Overcoming Molochian Traps

China's high-speed rail (HSR) system represents a powerful counter-example to Molochian dynamics—a case where centralized, state-led coordination has produced outcomes that would be impossible under decentralized market incentives alone. This example is particularly instructive because it demonstrates how deliberate institutional design can overcome the coordination failures that plague infrastructure development in many market-oriented economies.

Scale and Speed of Development

The development of China's high-speed rail network has been unprecedented in both scale and speed. In just over a decade, China built the world's largest high-speed rail network from scratch:

In 2008, China had virtually no high-speed rail lines

By 2017, the network had grown to 25,000 kilometers, accounting for 66% of the world's total high-speed rail

By 2025, the network exceeded 40,000 kilometers, connecting all provincial capitals and cities with populations over 500,000

This rapid development required massive capital investment—estimated at over $1 trillion—and coordination across multiple provinces, ministries, and technical domains. Such investment would be extremely difficult to mobilize through decentralized market mechanisms alone, particularly given the long payback periods and network externalities involved.

Poverty Alleviation and Regional Development

What makes China's HSR system particularly relevant as an anti-Molochian case is its explicit connection to poverty alleviation and balanced regional development. Unlike market-driven transportation investments that typically focus on high-traffic, profitable routes between wealthy regions, China's HSR network was deliberately designed to connect less-developed regions to economic centers.

Research published in the journal Land (2022) analyzed the relationship between HSR development, inter-county accessibility improvements, and regional poverty alleviation in China. The study found that HSR significantly improved accessibility for previously isolated counties and contributed to poverty reduction, particularly in regions targeted by China's national poverty alleviation campaign.

The World Bank, in its comprehensive 2019 report "China's High-Speed Rail Development," concluded that "HSR can contribute to rebalancing growth geographically to reduce poverty and enhance inclusiveness." The report noted that the economic results "appear positive, even at this early stage," with benefits including:

Improved market access for businesses in smaller cities

Enhanced labor mobility between regions

Reduced economic isolation of rural areas

Technology transfer and industrial upgrading in previously underdeveloped regions

Overcoming Molochian Dynamics

The development of China's HSR system directly counters several Molochian traps that typically prevent optimal infrastructure development:

The long-term investment trap: Private investors typically demand returns within 3-7 years, making it difficult to finance infrastructure with 30+ year lifespans. China's state-led approach enabled investment with much longer time horizons.

The network externality trap: The value of any single HSR line depends on the existence of a broader network, creating a chicken-and-egg problem for incremental development. China's comprehensive planning approach allowed for simultaneous development of multiple lines to maximize network effects.

The regional coordination trap: Infrastructure crossing multiple jurisdictions creates incentive problems when costs and benefits are unevenly distributed. China's centralized planning process enabled optimization at the national rather than local level.

The equity-efficiency trap: Market-driven infrastructure typically prioritizes efficiency (serving wealthy, high-density areas) over equity (connecting poorer regions). China's approach explicitly balanced these objectives, using cross-subsidization to serve less profitable routes.

Institutional Mechanisms

The success of China's HSR system wasn't simply a matter of authoritarian fiat but involved specific institutional mechanisms that enabled coordination:

Vertical integration: The Ministry of Railways (later reorganized) controlled planning, construction, and operation, reducing transaction costs and principal-agent problems.

Land acquisition powers: The state's ability to acquire land at administratively determined prices overcame the holdout problems that plague infrastructure development in market economies.

Cross-subsidization: Profitable eastern routes helped finance less profitable western and central routes, enabling network completion rather than cherry-picking.

Technical standardization: China rapidly developed and standardized HSR technology, allowing for economies of scale in production and maintenance.

Limitations and Criticisms

While China's HSR system demonstrates the potential of coordinated planning to overcome Molochian traps, it's important to acknowledge limitations and criticisms:

Debt concerns: Some lines, particularly in less-developed regions, may never achieve financial sustainability, raising questions about long-term debt burdens.

Environmental impacts: Rapid construction has sometimes outpaced environmental assessment processes.

Displacement issues: Land acquisition has occasionally led to controversial relocations of communities.

Opportunity costs: The massive investment in HSR necessarily meant fewer resources for other potential priorities.

Broader Implications

China's HSR experience suggests that overcoming Molochian dynamics in infrastructure development may require institutional innovations that enable longer time horizons, internalize externalities, and balance efficiency with equity concerns. While China's specific approach reflects its unique political and economic context, the general principles of coordination could inform infrastructure development strategies in other settings.

The case also highlights that different domains may require different balances between market mechanisms and coordinated planning. Transportation infrastructure, with its long time horizons, network effects, and broad social benefits, may be particularly suited to more coordinated approaches than domains where consumer preferences change rapidly or innovation depends on decentralized experimentation.

In the context of our broader discussion of Molochian dynamics, China's HSR system demonstrates that with appropriate institutional design, societies can overcome the coordination failures that otherwise lead to collectively suboptimal outcomes. The challenge lies in developing institutions that enable this coordination while maintaining adaptability, accountability, and respect for individual rights—a challenge that different societies will necessarily approach in different ways based on their own historical, cultural, and political contexts.

Alternative Sources of Inspiration for Overcoming Molochian Dynamics

Indigenous Governance Systems: Consensus-Based Decision Making

Indigenous governance systems across the world offer profound insights into alternative approaches for addressing Molochian dynamics. These systems, developed over thousands of years, have successfully managed common resources and maintained social cohesion through practices that prioritize collective well-being over individual gain. Central to many of these governance systems is the practice of consensus-based decision making, which stands in stark contrast to the majoritarian voting mechanisms that dominate modern political institutions.

Traditional consensus decision making, as practiced by many Indigenous communities, represents a fundamentally different approach to collective governance. Rather than simply aggregating individual preferences through voting—a process that can exacerbate divisions and create winners and losers—consensus processes work to synthesize the wisdom of the community as a whole. Issues are raised, discussed, and resolved as the community moves toward a shared understanding and agreement.

As noted by the Report of the Royal Commission of Aboriginal Peoples, "The art of consensus decision making is dying. We are greatly concerned that Aboriginal people are increasingly equating 'democracy' with the act of voting... We are convinced that the practice of consensus decision making is essential to the culture of our peoples, as well as being the only tested and effective means of Aboriginal community self-government."

Importantly, consensus does not require unanimity. Rather, it involves a process where community members listen to the opinions and concerns of others and work toward a suitable decision that, while perhaps not pleasing everyone, is recognized as the best decision for the community as a whole. This approach acknowledges the inherent complexity of social problems and the limitations of any single perspective.

As one Indigenous elder, Peter O’chiese, eloquently explained: "Seven perspectives blended, seven perspectives working in harmony together to truly define the problem, truly define the action that is needed makes for an eighth understanding. It's a tough lesson that we don't know all the answers, we don't know all the problems. We really own only one-seventh of the understanding of it and we only know one-seventh of what to do about it. We need each other in harmony to know how to do things... This process that we had was 100 per cent ownership of the problem."

This approach to decision making embodies several principles that directly address Molochian dynamics:

Long-term thinking: Many Indigenous governance systems incorporate the "Seventh Generation Principle," which requires decision-makers to consider how their actions will affect people seven generations in the future—approximately 140 years. This temporal horizon stands in stark contrast to the short-term incentives that drive many Molochian traps.

Relational accountability: Leadership in Indigenous communities is often understood not as power over others but as responsibility to others. Leaders are accountable to their communities, to future generations, and to the natural world. This relational understanding of governance helps align individual incentives with collective welfare.

Integrative rather than extractive relationship with nature: Many Indigenous governance systems reject the separation between human societies and natural systems, instead viewing humans as embedded within and responsible to the natural world. This perspective helps address the externalities that drive environmental Molochian dynamics.

Deliberative processes: Consensus-based decision making requires extensive deliberation, ensuring that diverse perspectives are heard and integrated. This helps overcome the information asymmetries and narrow optimization that characterize Molochian systems.

The relevance of these approaches extends beyond Indigenous communities. Elements of consensus-based governance have been successfully incorporated into various modern contexts, from community organizations to international environmental agreements. The challenge lies in adapting these principles to larger-scale governance challenges while preserving their essential characteristics.

Cooperative Economic Models: Reimagining Ownership and Control

Cooperative economic models offer another rich source of inspiration for addressing Molochian dynamics, particularly in economic contexts. These models reimagine the fundamental structures of ownership and control that shape economic activity, creating alternatives to the shareholder primacy model that drives many contemporary Molochian traps.

At their core, cooperatives are enterprises owned and democratically controlled by their members, who can be workers, consumers, producers, or some combination thereof. This structure fundamentally alters the incentives facing the organization, as the people who make decisions are also those who bear the consequences of those decisions. This alignment helps overcome the principal-agent problems and externalities that characterize many Molochian dynamics.

The Mondragón Cooperative Corporation in Spain's Basque region represents perhaps the most successful large-scale implementation of cooperative principles. Founded in 1956, Mondragón has grown to become Spain's tenth-largest business group, with over 80,000 employee-owners working across manufacturing, retail, finance, and knowledge sectors. Despite its size and complexity, Mondragón maintains a democratic governance structure and a commitment to social responsibility.

Several features of the Mondragón model address Molochian dynamics:

Democratic governance: Major decisions are made on a one-person, one-vote basis, regardless of position or tenure. This prevents the concentration of decision-making power that often drives Molochian traps.

Solidarity in compensation: The ratio between the highest and lowest paid workers is limited (typically to around 6:1, compared to ratios exceeding 300:1 in many conventional corporations). This reduces the incentives for executives to prioritize short-term gains over long-term sustainability.

Intercooperation: Mondragón cooperatives support each other through shared services, financial solidarity, and knowledge exchange. This network structure helps overcome the competitive pressures that often drive race-to-the-bottom dynamics.

Commitment to community: Cooperatives allocate a portion of their surplus to community development, education, and social initiatives. This institutionalizes consideration of broader social impacts beyond narrow financial metrics.

Beyond Mondragón, cooperative principles have been successfully applied across diverse sectors and scales. The Italian region of Emilia-Romagna has developed a thriving network of small and medium-sized cooperatives that collectively employ hundreds of thousands of people. In the United States, worker cooperatives like Equal Exchange (fair trade food) and Cooperative Home Care Associates (home healthcare) demonstrate the viability of cooperative models in contemporary market contexts.

The solidarity economy movement extends cooperative principles beyond individual enterprises to envision interconnected ecosystems of democratic economic institutions. This approach includes credit unions, community land trusts, mutual aid networks, and other structures that prioritize meeting human needs over maximizing returns to capital. By creating economic spaces governed by different logics and incentives, these initiatives offer practical alternatives to Molochian dynamics.

Importantly, cooperative models do not require wholesale replacement of existing economic systems to offer valuable insights. Hybrid models like benefit corporations, employee ownership plans, and multi-stakeholder governance structures can incorporate cooperative principles within conventional legal frameworks. These approaches offer pathways for incremental transformation rather than requiring revolutionary change.

Commons-Based Governance: Lessons from Elinor Ostrom

Elinor Ostrom's groundbreaking research on commons governance provides another rich source of inspiration for addressing Molochian dynamics. Challenging the conventional wisdom that common-pool resources inevitably face a "tragedy of the commons," Ostrom documented numerous cases where communities successfully managed shared resources through locally developed institutional arrangements.

Ostrom's work identified several design principles that characterize successful commons governance:

Clearly defined boundaries: Successful commons clearly define who has rights to withdraw resources and the boundaries of the resource itself.

Congruence with local conditions: Rules governing resource use are tailored to local ecological and social conditions rather than imposed from outside.

Collective-choice arrangements: Most individuals affected by operational rules can participate in modifying those rules, creating ownership of the governance process.

Monitoring: Those who monitor resource conditions and user behavior are accountable to the users or are the users themselves.

Graduated sanctions: Violations of rules are addressed with graduated sanctions that reflect the seriousness and context of the offense.

Conflict-resolution mechanisms: Users and officials have rapid access to low-cost arenas for resolving conflicts.

Recognition of rights to organize: The rights of users to devise their own institutions are not challenged by external governmental authorities.

Nested enterprises: For larger systems, governance activities are organized in multiple, nested layers.

These principles directly address many of the mechanisms that drive Molochian dynamics. By ensuring that those affected by rules can participate in making them, commons governance helps align individual incentives with collective welfare. By tailoring rules to local conditions and enabling adaptive management, it addresses the information constraints that often lead to suboptimal outcomes. And by establishing graduated sanctions and conflict-resolution mechanisms, it creates feedback systems that can correct harmful behaviors before they become systemic.

Ostrom's approach emphasizes that neither pure market solutions nor top-down state control are necessary or sufficient conditions for sustainable resource management. Instead, she documented the effectiveness of polycentric governance—systems with multiple centers of decision-making authority operating with some degree of autonomy but also coordinating with each other. This polycentric approach offers a middle path between the fragmentation of pure market systems and the rigidity of centralized control.

Contemporary applications of Ostrom's insights extend beyond traditional natural resource commons to address new challenges. The digital commons movement, exemplified by open-source software and Wikipedia, applies commons governance principles to knowledge and information resources. Urban commons initiatives reimagine city spaces and services as collectively governed resources rather than either private or state property. And emerging climate governance frameworks increasingly incorporate polycentric approaches that enable coordination across multiple scales while respecting local autonomy.

Regenerative Economics: Beyond Growth and Extraction

Regenerative economics offers yet another perspective on overcoming Molochian dynamics by reimagining the fundamental purpose and design of economic systems. Moving beyond both conventional growth-oriented economics and simple sustainability, regenerative approaches seek to design economic activities that actively restore and regenerate the social and ecological systems upon which they depend.

Several key principles characterize regenerative economic thinking:

Circularity: Rather than the linear "take-make-waste" model that characterizes industrial economies, regenerative approaches design for circularity, where outputs from one process become inputs for another, mimicking natural cycles.

Nested value creation: Regenerative economics recognizes that economic value is created within and dependent upon social systems, which in turn exist within and depend upon ecological systems. This nested understanding helps address the externalities that drive many Molochian dynamics.

Place-based design: Regenerative approaches emphasize adaptation to the specific ecological and social contexts of particular places, rather than imposing standardized solutions. This helps overcome the information constraints that often lead to suboptimal outcomes.

Relationship-centered metrics: Rather than focusing narrowly on financial returns or even triple-bottom-line accounting, regenerative approaches measure success by the health and vitality of relationships—between people, between enterprises, and between human and natural systems.

Practical applications of regenerative economics include regenerative agriculture, which builds soil health while producing food; living building design, which creates structures that generate more energy than they use and process their own waste; and regenerative finance, which directs capital toward enterprises that restore rather than deplete natural and social capital.

The work of economist Kate Raworth on "Doughnut Economics" offers a compelling framework for regenerative economic thinking. Raworth envisions an economy that meets the needs of all people while respecting planetary boundaries—creating a "safe and just space for humanity" represented visually as a doughnut. This framework directly addresses the Molochian dynamics that drive both ecological overshoot and human deprivation, offering a positive vision of prosperity within limits.

Spiritual and Philosophical Traditions: Beyond Material Incentives

Various spiritual and philosophical traditions offer profound insights into overcoming the narrow self-interest that drives many Molochian dynamics. While Confucian ethics provides one such perspective, many other traditions offer complementary approaches to cultivating virtues and practices that align individual behavior with collective flourishing.

Buddhist economics, as articulated by E.F. Schumacher and others, emphasizes the importance of "right livelihood" and the cultivation of mindfulness and compassion in economic activities. This approach challenges the assumption that human well-being is primarily a function of material consumption, instead emphasizing the quality of relationships and the development of inner capacities for contentment and care.

The Ubuntu philosophy from southern Africa, often summarized as "I am because we are," offers a relational understanding of personhood that stands in stark contrast to Western individualism. This perspective recognizes that human identity and flourishing are inherently social, dependent on relationships with others. As Archbishop Desmond Tutu explained, "A person with ubuntu is open and available to others, affirming of others, does not feel threatened that others are able and good, for he or she has a proper self-assurance that comes from knowing that he or she belongs in a greater whole."

Islamic economic principles, including the prohibition of interest (riba) and the requirement of charitable giving (zakat), offer another approach to aligning economic activity with broader ethical considerations. Islamic finance has developed sophisticated instruments that enable capital formation and investment without the extractive dynamics often associated with conventional finance.

These diverse traditions share a recognition that human flourishing requires more than material prosperity and that narrow self-interest is ultimately self-defeating. By cultivating virtues like compassion, generosity, and mindfulness, these approaches address the deeper cultural and psychological drivers of Molochian dynamics.

Integrative Approaches: Combining Multiple Perspectives

Perhaps the most promising path forward lies not in choosing any single alternative to current systems but in thoughtfully integrating insights from multiple traditions and approaches. Different Molochian dynamics may require different interventions, and complex challenges often demand multifaceted responses.

For example, addressing climate change might involve:

Indigenous perspectives on long-term thinking and relational accountability to future generations and the natural world.

Cooperative economic models that align enterprise incentives with ecological health.

Commons-based governance approaches for managing atmospheric carbon and other shared resources.

Regenerative design principles for reimagining energy, transportation, and food systems.

Spiritual and philosophical insights that help cultivate the virtues needed for collective action and shared sacrifice.

This integrative approach recognizes that Molochian dynamics operate across multiple dimensions—economic, political, cultural, and psychological—and therefore require responses that address all these dimensions. It also acknowledges that different cultural and historical contexts may call for different combinations of approaches, avoiding the trap of imposing one-size-fits-all solutions.

The challenge lies in creating spaces for genuine dialogue and learning across these diverse traditions, enabling the emergence of new syntheses that draw on the wisdom of multiple perspectives while remaining attentive to specific contexts and challenges. This process of dialogue and integration represents not just an intellectual exercise but a practical necessity for addressing the complex, interconnected Molochian dynamics that threaten human and ecological flourishing in the 21st century.

Discussion: Breaking the Molochian Trap

Addressing Molochian dynamics requires interventions that fundamentally realign incentives, transform institutional structures, and cultivate new forms of leadership and governance. This section explores four complementary approaches to breaking Molochian traps:

Institutional design innovations

Confucian ethical frameworks

China’s state-led coordination models

Game B: A Civilizational Reset (Informed by Proven Models)

Each offers distinctive insights and mechanisms for overcoming the coordination failures that characterize Molochian systems.

1. Institutional Design Innovations

Institutional design represents the most widely explored approach to addressing coordination problems in Western scholarly and policy contexts. At its core, institutional design seeks to create structures that align individual incentives with collective welfare, often through formal rules, incentives, and enforcement mechanisms.

Key Innovations

Supranational Treaties: Agreements like the Paris Climate Accord aim to overcome free-rider problems by establishing binding commitments, monitoring mechanisms, and mutual obligations. While limited by sovereignty concerns and weak enforcement, such treaties demonstrate how institutional design can internalize global externalities (e.g., carbon emissions).

Impact-Weighted Accounting: This approach incorporates social and environmental costs into financial statements, making previously invisible externalities (e.g., pollution, labor exploitation) visible to investors and decision-makers. By aligning financial metrics with systemic health, it challenges shareholder primacy and encourages long-term thinking.

Benefit Corporations: These legal frameworks allow companies to pursue social and environmental objectives alongside profit without risking shareholder lawsuits. By redefining fiduciary duties, benefit corporations create space for stakeholder governance in market-driven systems.

Case Studies

Climate Governance: Carbon pricing mechanisms (e.g., cap-and-trade systems) exemplify institutional design’s potential to internalize externalities, though their effectiveness depends on enforcement and political will.

Corporate Governance: Extended producer responsibility laws (e.g., requiring manufacturers to manage product lifecycles) illustrate how institutional design can address market failures by closing feedback loops between production and environmental impact.

2. Confucian Ethical Frameworks

Confucian ethics offers a philosophical tradition rooted in relational harmony (和, hé ) and moral cultivation (君子, jūnzǐ ). Unlike Western liberal individualism, which prioritizes institutional constraints on power, Confucian thought emphasizes the cultivation of virtue in leadership to align individual actions with collective flourishing.

Core Principles

Relational Accountability: Leadership is defined not by authority over others but by responsibility to them. This contrasts with shareholder primacy, where executives prioritize short-term profits over stakeholder well-being.

Long-Term Stewardship: Confucian emphasis on multi-generational planning mirrors the Seventh Generation Principle in Indigenous governance, fostering resilience against short-term optimization.

Ritual and Role Ethics (禮, lǐ): Social roles are understood as dynamic, interdependent relationships rather than rigid hierarchies. This framework encourages leaders to view their actions as part of a broader moral ecosystem.

Case Studies

UnitedHealthcare CEO Incident : Confucian relational accountability critiques the profit-driven healthcare model, urging insurers to prioritize patient welfare as a moral duty rather than transactional exchange.

Political Meritocracy: Daniel Bell’s analysis of China’s cadre training programs highlights how Confucian-inspired selection processes could cultivate leaders who resist Molochian pressures in domains like environmental policy or AI governance.

3. China’s State-Led Coordination Models

China’s high-speed rail (HSR) system exemplifies how centralized planning can enable strategic investments that market-based systems struggle to achieve. This model demonstrates the potential of state-led coordination to overcome Molochian traps through long-term vision, cross-subsidization, and nested governance.

Key Features

Five-Year Plans: These frameworks enable multi-decade strategic coordination across sectors (e.g., renewable energy, infrastructure), contrasting with electoral democracies constrained by short-term cycles.

Cross-Subsidization: Profitable eastern HSR routes fund unprofitable western routes, balancing efficiency with equity—a principle that could inform global climate finance.

Nested Governance: Centralized design with decentralized execution (e.g., provincial implementation of national plans) reduces transaction costs while enabling local adaptability.

Limitations and Critiques

Information Asymmetries: Centralized systems may lack the agility to respond to rapidly changing conditions (e.g., AI governance).

Authoritarian Risks: Without accountability mechanisms, top-down planning can entrench elite capture or prioritize growth over ecological health.

Case Studies

HSR and Poverty Alleviation: China’s HSR network demonstrates how state-led coordination can address regional inequality by connecting underdeveloped areas to economic hubs, countering the “regional coordination trap” described in the conceptual framework.

4. Game B: A Civilizational Reset Informed by Proven Models

Daniel Schmachtenberger’s Game B framework proposes a phase shift in human coordination, transcending incremental reforms to reimagine social systems at civilizational scale. Game B emphasizes decentralized, anti-rivalrous protocols that align individual and collective interests through systemic design.

Core Principles

Omni-Consideration: Systems designed to internalize all externalities, echoing impact-weighted accounting but scaling to ecological and social feedback loops.

Anti-Rivalrous Dynamics: Participants benefit from others’ success (e.g., cooperative finance, regenerative agriculture), contrasting Game A’s zero-sum logic.

Regenerative Design: Prioritizing systems that create positive externalities, informed by Indigenous stewardship practices and China’s cross-subsidization in HSR.

Cultural Synthesis

Confucian Ethics: Game B’s emphasis on sovereignty and sense-making aligns with jūnzǐ leadership, ensuring decentralized actors act with wisdom.

ASEAN Consensus: Anti-rivalrous dynamics mirror ASEAN’s non-hierarchical decision-making, avoiding winner-take-all outcomes.

Indigenous Governance: Regenerative design draws on Indigenous relational accountability to nature, rejecting extractive logics.

Case Studies

US-China Chip War: Game B proposes anti-rivalrous protocols for global tech cooperation, contrasting both nations’ zero-sum competition.

Healthcare: Regenerative design could reframe profit-driven systems toward wellness generation, complementing Confucian relational accountability critiques of insurer behavior.

Cultural, Regional and Civilizational Frameworks

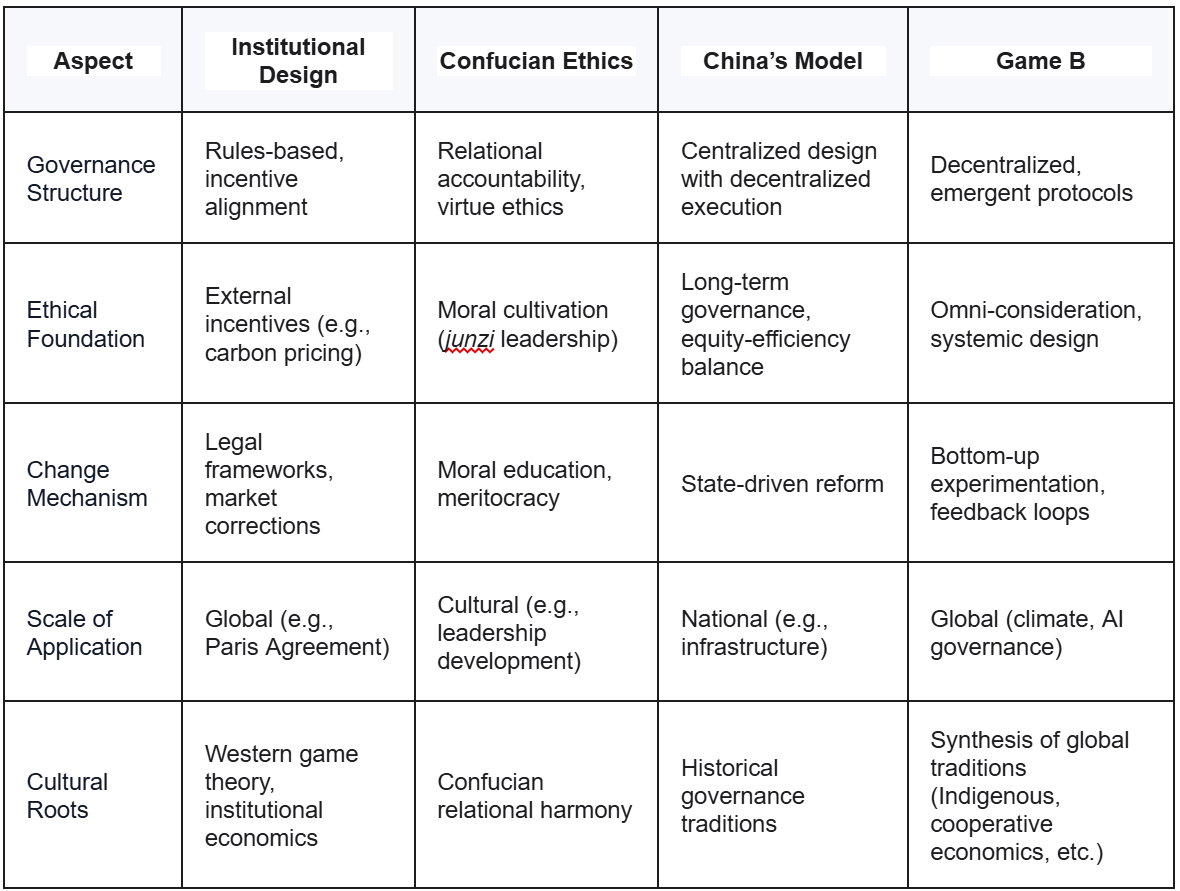

The table below compares the four approaches, emphasizing their distinct scales, governance philosophies, and cultural roots:

Notes

Complementary Scales: Institutional design operates globally (e.g., climate treaties), while Confucian ethics focuses on cultivating leaders to navigate local moral dilemmas (e.g., healthcare).

Hybridization Potential:

China’s Cross-Subsidization + Game B: China’s HSR model demonstrates anti-rivalrous dynamics, which Game B could scale through regenerative design.

Confucian Virtue Ethics + Game B: Moral cultivation ensures decentralized actors in Game B systems act with wisdom, avoiding fragmentation.

Cultural Pluralism: Each framework is rooted in distinct traditions—Western legalism, Confucian relationality, Chinese technocracy, and Game B’s synthesis of global models.

Challenges

Implementing solutions to Molochian dynamics faces several significant challenges that must be addressed for interventions to succeed. Perhaps most fundamentally, effective solutions require robust feedback and adaptation mechanisms to avoid rigidity and enable learning from experience. Elinor Ostrom's work on adaptive governance emphasizes how successful institutional arrangements evolve through iterative processes of experimentation, evaluation, and adjustment. This approach recognizes that complex social-ecological systems cannot be perfectly understood or controlled, making adaptive learning essential for effective governance. Solutions that lack these feedback mechanisms risk becoming rigid and unresponsive to changing conditions or unintended consequences.

Implementing effective feedback systems requires overcoming several obstacles. Information asymmetries can prevent accurate assessment of policy impacts, particularly when effects are delayed, diffuse, or difficult to measure. Power asymmetries can distort feedback processes, privileging the perspectives and interests of powerful actors while marginalizing those with less influence. Cognitive biases can lead decision-makers to selectively attend to information that confirms existing beliefs while discounting contradictory evidence. Overcoming these obstacles requires deliberate attention to the design of feedback systems, including diverse information sources, transparent evaluation processes, and mechanisms for incorporating marginalized perspectives.

Cultural resistance represents another significant challenge to addressing Molochian dynamics. Populist politics often mobilize opposition to collective action frameworks by framing them as threats to national sovereignty, individual freedom, or traditional ways of life. Neoliberal ideologies that emphasize market solutions and minimal government intervention can similarly undermine support for the institutional innovations needed to address coordination failures. These cultural and ideological resistances are not merely intellectual disagreements but powerful social forces that shape political possibilities and constrain the range of feasible interventions.

Overcoming cultural resistance requires strategies that engage with deeply held values and identities rather than merely presenting technical solutions. This might involve framing collective action in terms that resonate with diverse value systems, building broad coalitions that transcend traditional political divides, and developing narratives that connect systemic change to widely shared aspirations for security, prosperity, and meaning. It also requires attention to the legitimate concerns that sometimes underlie resistance to change, including fears about loss of autonomy, cultural identity, or economic security. By addressing these concerns directly rather than dismissing them, advocates for systemic change can potentially build broader support for the transformations needed to address Molochian dynamics.

The global nature of many Molochian problems creates additional challenges for effective intervention. Climate change, financial system stability, pandemic prevention, and other critical challenges transcend national boundaries, requiring coordination across diverse political, economic, and cultural contexts. This global scale exacerbates many of the coordination problems discussed throughout this paper, as the number of actors increases, feedback loops become more complex, and institutional design must accommodate greater diversity. Moreover, power asymmetries between nations create additional obstacles to equitable and effective global governance, as powerful actors can often shape rules and institutions to serve their interests at the expense of others. Addressing these global challenges requires innovative approaches to governance that can facilitate coordination while respecting diversity and sovereignty concerns.

Conclusion

Molochian dynamics reflect a meta-crisis of decentralized incentives and institutional misalignment that manifests across diverse domains of human activity. Throughout this paper, we have examined how these dynamics emerge not from malice or conspiracy but from structural incentives that reward short-term optimization at the expense of collective welfare.

The resulting coordination failures—from environmental degradation to arms races, from technological risks to financial instabilities—represent perhaps the defining governance challenge of our time. Addressing these challenges requires moving beyond simplistic narratives of villains and heroes to understand the systemic nature of the problems we face.

Our analysis has revealed several key insights about the nature of Molochian dynamics.

These systems exhibit emergent properties that cannot be reduced to the intentions or actions of any individual actor. Even powerful participants find themselves constrained by competitive pressures and systemic incentives that limit their ability to unilaterally change course.

These dynamics are reinforced through multiple mechanisms—perverse incentives, path dependencies, feedback loops, and information constraints—that create robust systems resistant to reform.

These challenges transcend traditional disciplinary boundaries, requiring analytical frameworks that integrate insights from game theory, political economy, complex systems theory, and normative philosophy.

Escaping Molochian traps demands reimagining governance through four complementary approaches, each offering distinct tools for systemic redesign:

Technocratic Coordination: Exemplified by China’s state-led model, centralized planning enables strategic investments and long-term thinking that market-based systems often struggle to achieve. China’s high-speed rail system demonstrates how deliberate institutional design can overcome regional coordination traps and equity-efficiency trade-offs, though centralized approaches must balance accountability and adaptability to avoid rigidity and elite capture.

Ethical Leadership: Grounded in Confucian virtue ethics, this approach emphasizes moral cultivation and relational accountability as prerequisites for aligning individual and collective interests. The Confucian ideal of the junzi (君子) highlights how leaders prioritizing long-term stewardship over narrow self-interest can counteract Molochian pressures in domains like healthcare and climate governance.

Game B: A Civilizational Reset: Daniel Schmachtenberger’s framework proposes a systemic redesign of social systems through principles like omni-consideration, anti-rivalrous dynamics, and regenerative design. Unlike incremental reforms, Game B envisions a phase shift in human coordination by synthesizing proven models—from Indigenous relational accountability to ASEAN consensus—to create decentralized protocols that align individual and collective flourishing.

Hybridization and Cultural Pluralism: The comparative framework underscores that no single approach suffices. Institutional design innovations (e.g., impact-weighted accounting) must be contextualized alongside culturally rooted traditions (e.g., ASEAN’s non-hierarchical dialogue) and experimental models like Game B. This pluralistic perspective rejects one-size-fits-all solutions, advocating instead for hybrid frameworks that adapt to specific domains and scales.